ABOUT

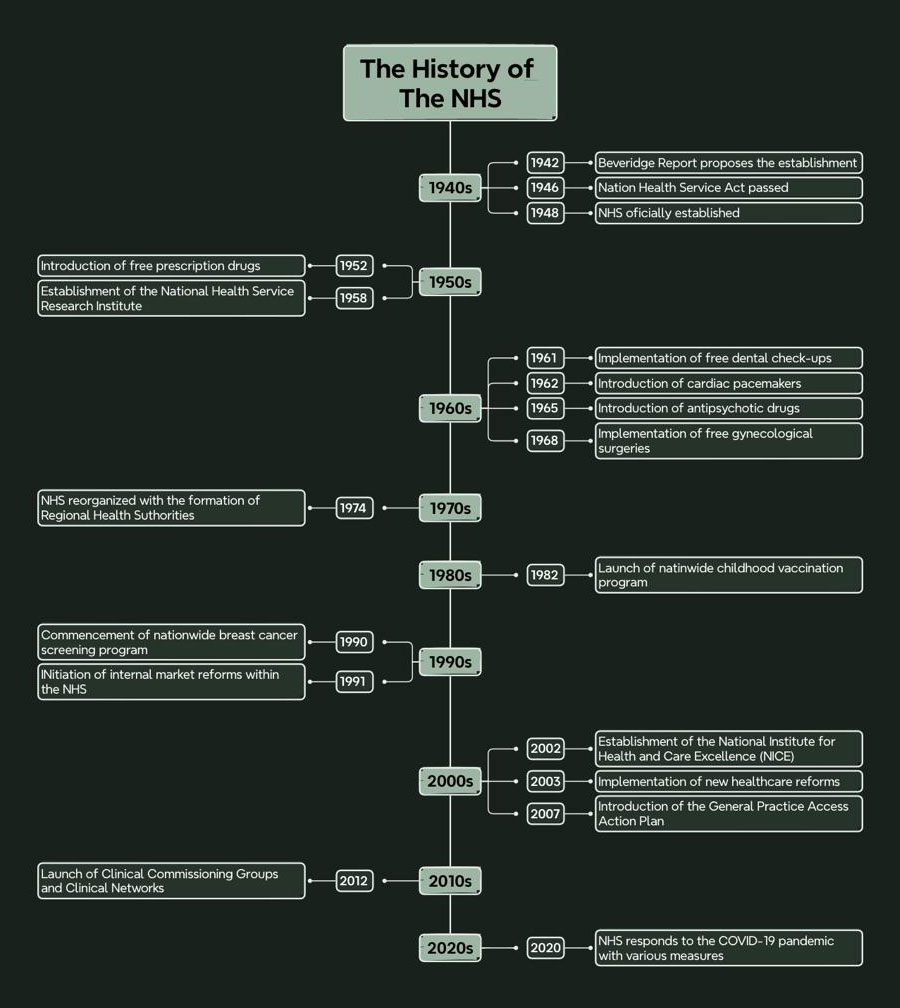

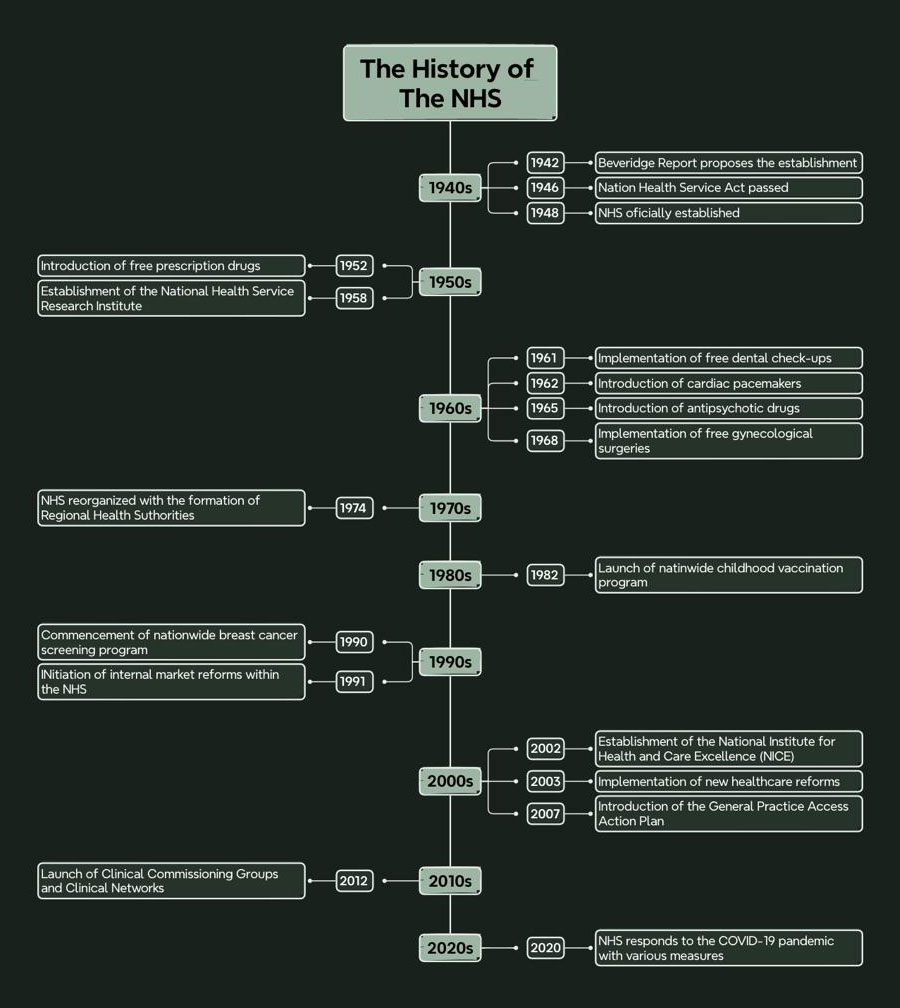

The History of The NHS

The 1880s in Britain was called the Victorian era, a time when the Industrial Revolution dramatically changed the social structure and the way people lived. As for women, this period marked the initial expansion of their opportunities to participate in professional work, although it was severely limited by gender roles and social expectations.

The gender inequality of workers in Britain began in the Victorian British Era (1873-1902), first and foremost in terms of socio-economic context. Due to financial barriers, lack of access to educational resources and limited exposure to the profession, some nursing tasks have been categorised as female tasks since males were considered to undertake physical work. This not only locked women into the caring occupation which they hardly could seek for other kinds of jobs, but also potentially discouraged men from pursuing nursing due to stereotypes about masculinity and caregiving.

Understanding such divides is quite important because it shows us how deep-rooted biases and norms have formed the basis of professional opportunities and treatment within the field. Studying UK nursing as a case study demonstrates the value of a context-sensitive approach to understanding the gains and the obstacles on the way to gender equality in healthcare. The reason why women preferred to choose nursing training is mainly because of the context and social structure of the Victorian British period.

RESEARCH

Historical Context of Gender Roles

in the UK Medical Care

The UK medical profession in the Victorian British Era (VBE) was affected by the status quo of rigid gender codes that placed women mostly in the role of taking care of others and giving help. The nursing job, which Florence Nightingale’s contribution crystallises, is representative of the process of such development and phenomenon. Nightingale’s plan of the Nightingale Training School for Nurses in 1860 was an event that changed the role of nursing from mundane tasks to a formalised education. Here, only women were targeted since they were considered a part of society relating to caregiving jobs (McEnroe, 2020). This education therefore expressed itself in the approval of the period’s gender bias which to a large extent led to the development of nursing as one that was intertwined with particularly noble gender expressions.

This historical rewriting sometimes mirrors the existing biases whereby major historical events are documented alternately to reinforce the established social norms or challenge the status quo. Thus, there was a considerable imbalance between women’s roles in nursing and their recognition, as they were often presented as subordinate contributors, or, were oversimplified in a historical context (Peličić, 2020). This may not depict a good picture of the complex nature of women’s participation in the nursing area. The problematic distortions in the contemporary sources point to the necessity of a critical examination of 19th-century records to reveal the true picture of the gender roles in the medical care practice during that epoch.

Contemporary Gender Dynamics in UK Healthcare

Modern gender relations in healthcare in the UK have come a long way since historical practices, however, many obstacles still need to be dealt with. The medical landscape now shows a growing number of women in nursing, yet there seems to be an insufficient number of women who are represented in top positions involving surgical services and hospital administration (Paton et al., 2020). Among the evident gender inequality, legislation on the Equality Act 2010 that reviews and amends discriminatory work practices is introduced to take away gender discrimination in healthcare.

It is a positive step that the modern workplace policy is in favour of flexible working arrangements and considers supporting female healthcare professionals by having maternity support. These developments are accompanied by a similar transition in social perceptions, which are gradually changing towards workplaces that create a level of gender playing field (Gebbels, Gao and Cai, 2020).

While this is a piece of encouraging news, challenges like pay disparities, glass ceiling hindrances, and persistent stereotypes about what are deemed the right jobs for men and women in the medical world are still being entertained. The UK is an example of the trend in Europe in which we can observe that the culture of healthcare is also largely female as women are dominant in nursing but do not occupy important medical roles (Gill and Baker, 2021). But countries like Sweden and Finland have a better mechanism of gender parity in terms of women leading the healthcare sector where they are very advanced. Such different hypotheses arise from the diversity evident in Europe when it comes to gender equality in healthcare sectors.

Gender Discrimination in Global Contexts

Unfair treatment of women in the healthcare sector goes up in many parts of Asia, affecting segments of society, including gender, economic, and social. Gender inequality is oftentimes represented in the medical professions of Asia where women are consigned to lower grades and lower-paid health professions, such as nurses, while surgery is mostly performed by men (Lim et al., 2021).

The perception of men being only full-time drivers while women are attending nurses and doing general hospital jobs stands in clear contrast to the UK and Europe, where both genders are more equally united to promote gender equality in healthcare services at all levels. The situation of women in healthcare leadership is different in countries like India or China and contains significant gender disparities as well (Hue et al., 2021).

Women are usually underrepresented in decision-making compared to European countries. This difference illustrates the approach lies in the development of policies globally, which target cultural views and give equal chances to every healthcare employee irrespective of gender.

Conclusion

The course of gender roles in healthcare is not about the withdrawal of old biases, but it is the road to more fair practices. Regardless, inequalities still exist today. A deep investigation into historical and contemporary statistics is crucial to comprehending and analysing these inequalities. The research and policies of tomorrow ought to aim at eradicating women’s binary in healthcare; this is the only way of taking into account the point of equity and efficiency throughout the different levels of medical professions.

DATA

Introduction

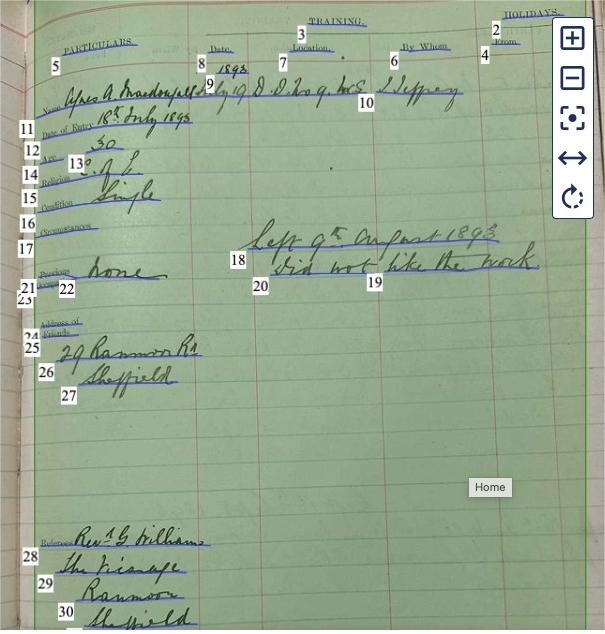

In this section, we explore the truths hidden within the data, supported by both literature and historical records. We utilize the original Nurse Training Register from Leeds General Infirmary during the Victorian British Era (VBE) to examine the foundations of nurse training in the UK. By organizing and analyzing these records, we have identified key patterns and trends that reveal the evolution of training practices and potential inequalities in the field over time.

Moreover, we have sourced contemporary data to compare with these historical records, aiming to trace the development of nurse training in the UK up to the present day. This comparison allows us to investigate persistent inequalities within the field. By employing a practical and objective approach, we transform these insights into visualizations that make the differences and developments between past and present both clear and intuitively understandable.

Combined with a thorough literature review, this analysis enriches our understanding of the era’s progression and the ongoing challenges in the field of nurse training. This dual historical and modern perspective provides a unique lens through which we can assess and discuss the broader implications of our findings.

Methodology in Focus:

Collecting and Describing Nurse Training Data

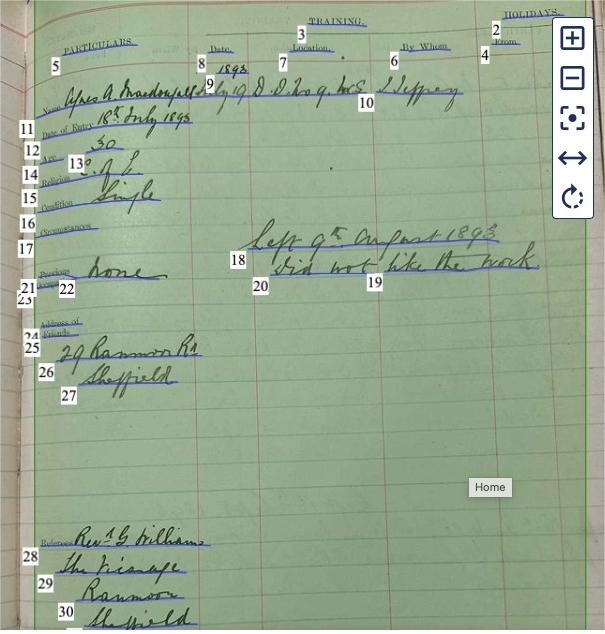

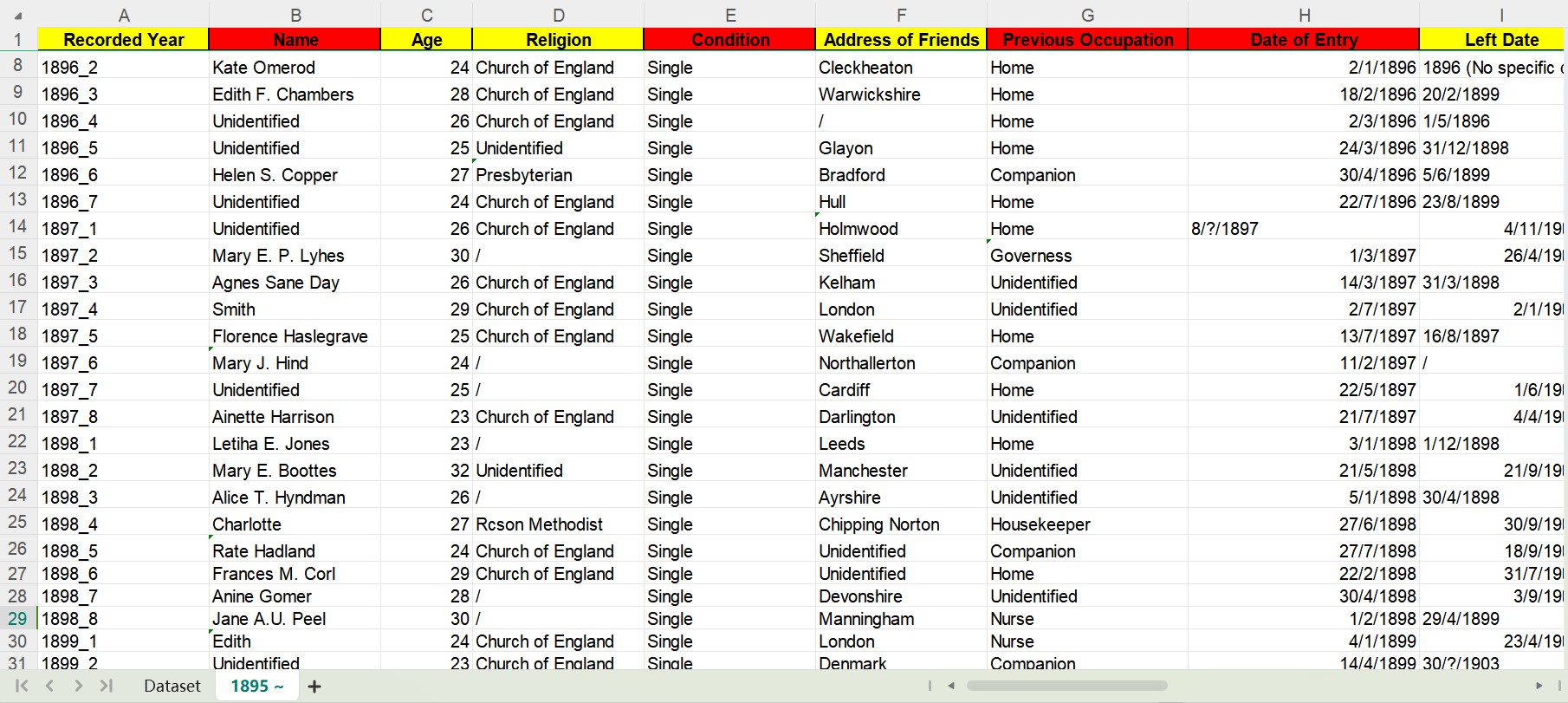

We sourced our historical data from a special collection at the University of Leeds, specifically focusing on a manuscript volume that details the training undertaken by nurse probationers at the Leeds General Infirmary during the Victorian British Era (VBE). This manuscript lists entries chronologically by date of enrollment, with each double-page spread featuring a printed form filled out with key information for each nurse: name, date of entry, age, religion, marital status (condition), circumstances, previous occupation, address of friends, and referees.

The condition of the manuscript, characterised by often indistinct or smeared handwriting, poses significant challenges for data transcription. To overcome these, we employed the Readcoop platform, enhancing our transcription accuracy with a nuanced understanding of the historical context and enabling a precise examination of potential inequalities related to gender, marital status, and religious affiliation.

Given the extensive span of the data, we employed a random sampling technique to manage its volume effectively. We selected samples from the years 1872 to 1903, covering a significant portion of the VBE. This approach allowed us to systematically collect, aggregate, catalogue, and exploit the data, revealing patterns in age, gender, marital status, religion, previous occupation, reasons for leaving, and duration of training.

Modern data is obtained from reliable online sources, such as official NHS reports and investigative journalism, focusing on indicators relevant to assessing inequality, such as gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and geographic distribution. This data is collected via internet searches, with direct quotations and secondary analyses conducted to facilitate a robust comparative analysis with historical data. This approach enables us to identify whether inequalities have persisted, lessened, or shifted in nature, offering a comprehensive view of trends and developments in nurse training.

Our analytical strategy highlights differences and continuities in nurse training from the Victorian era to the present, with a particular focus on inequality. Visualization techniques are employed not just for clarity and intuition but also to effectively communicate how inequalities in nurse training have evolved or remained consistent over time. These visual representations help the audience quickly understand complex data and trends, making the analysis more accessible and engaging than textual descriptions alone.

Visual Insights:

Analysing Inequalities in Nurse Training

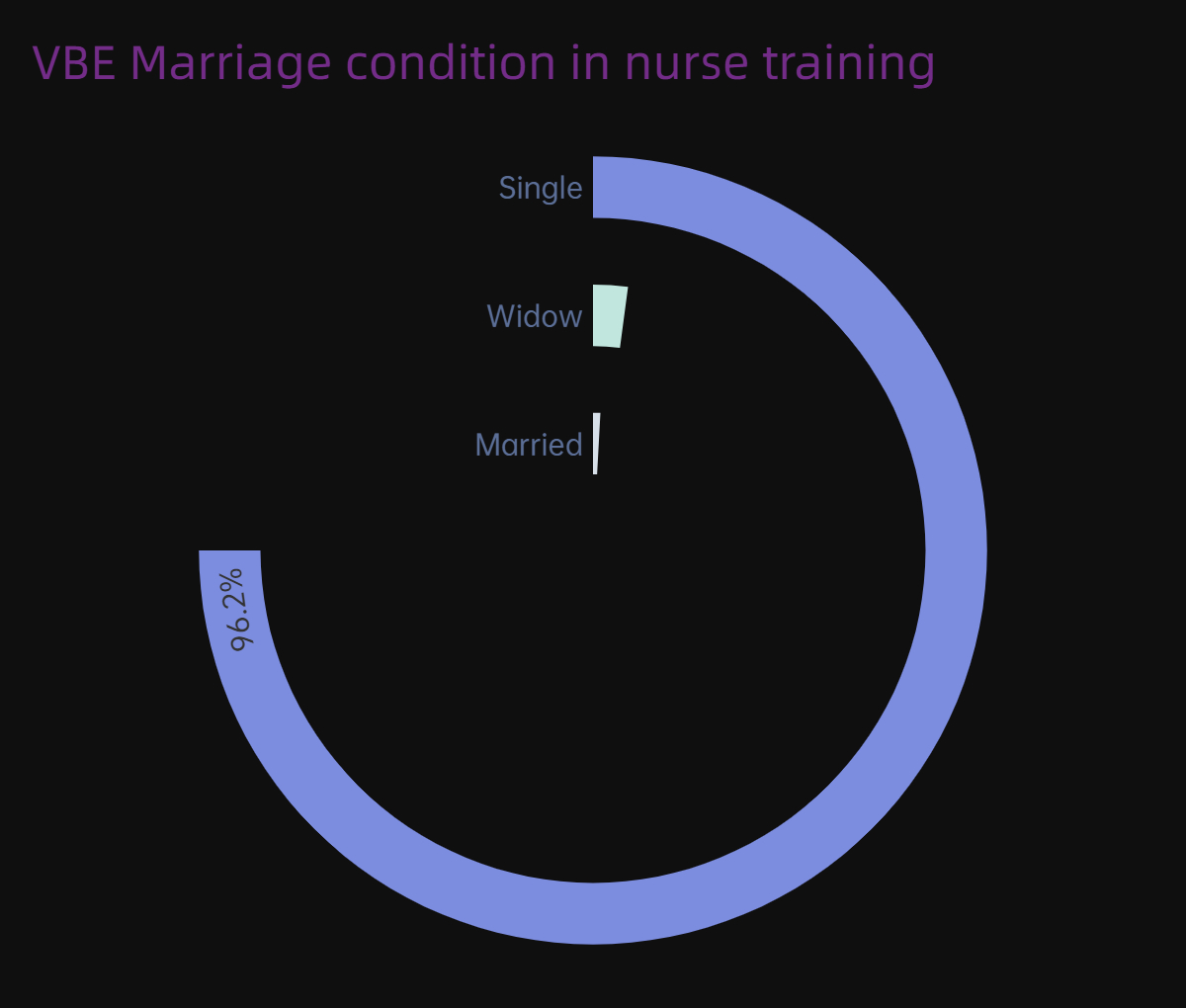

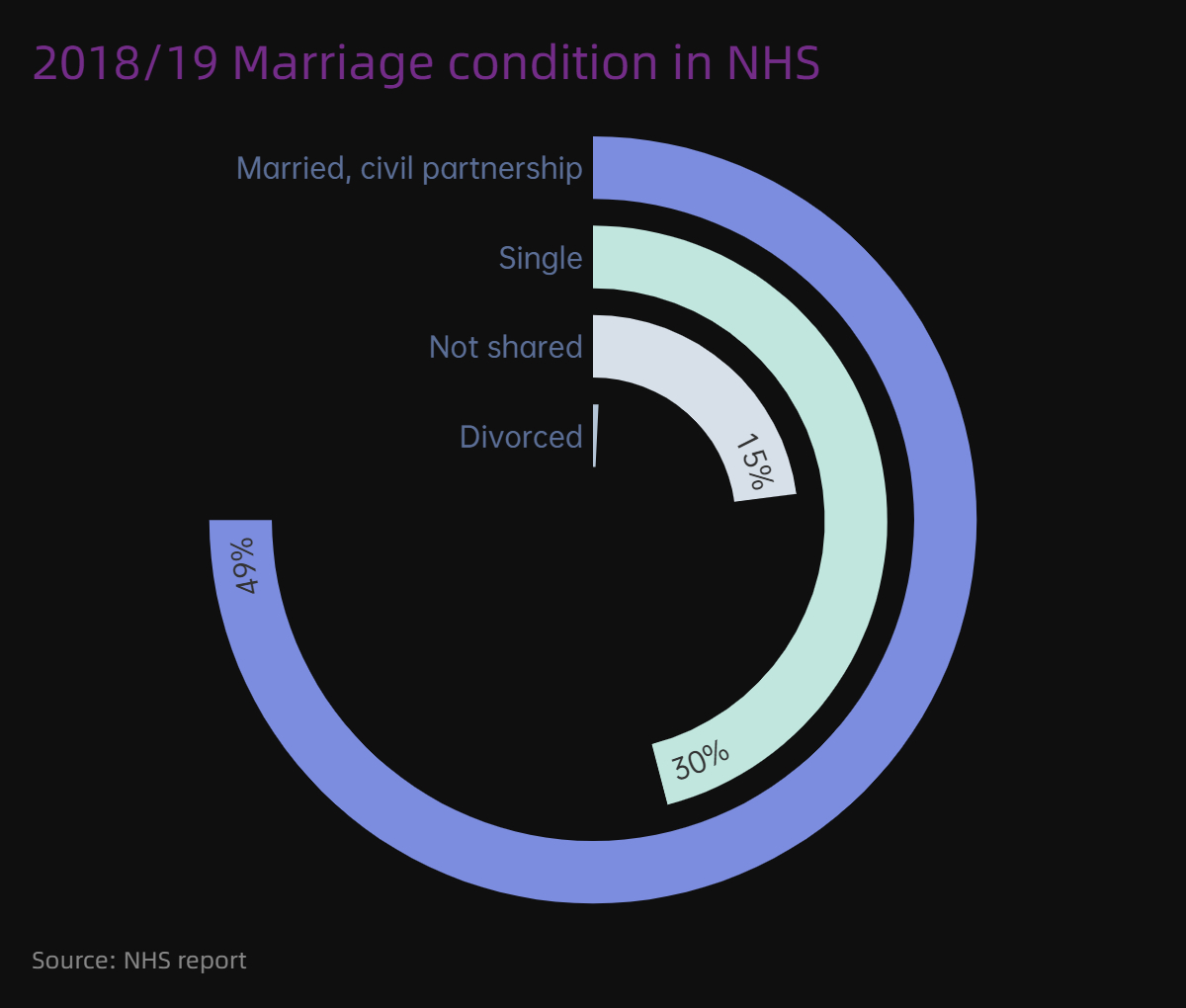

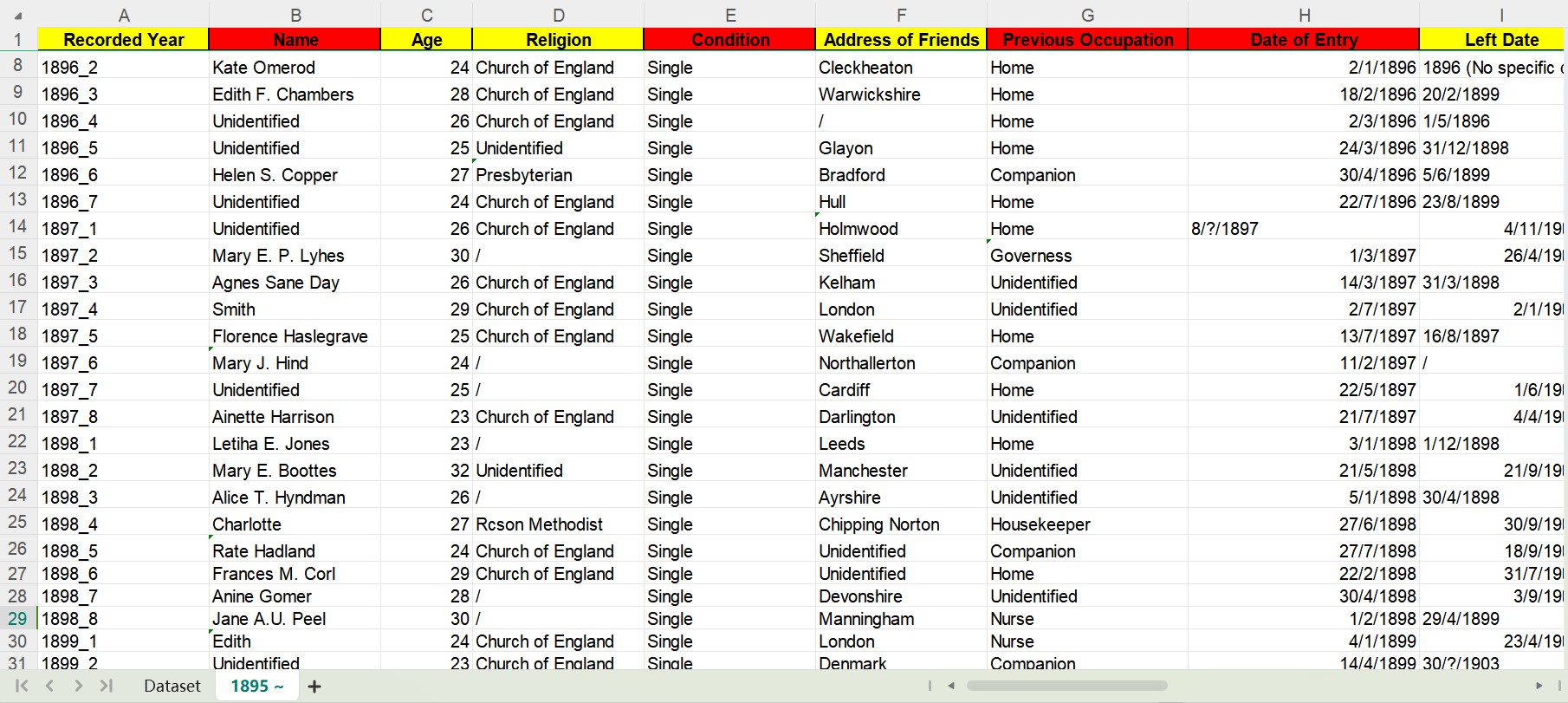

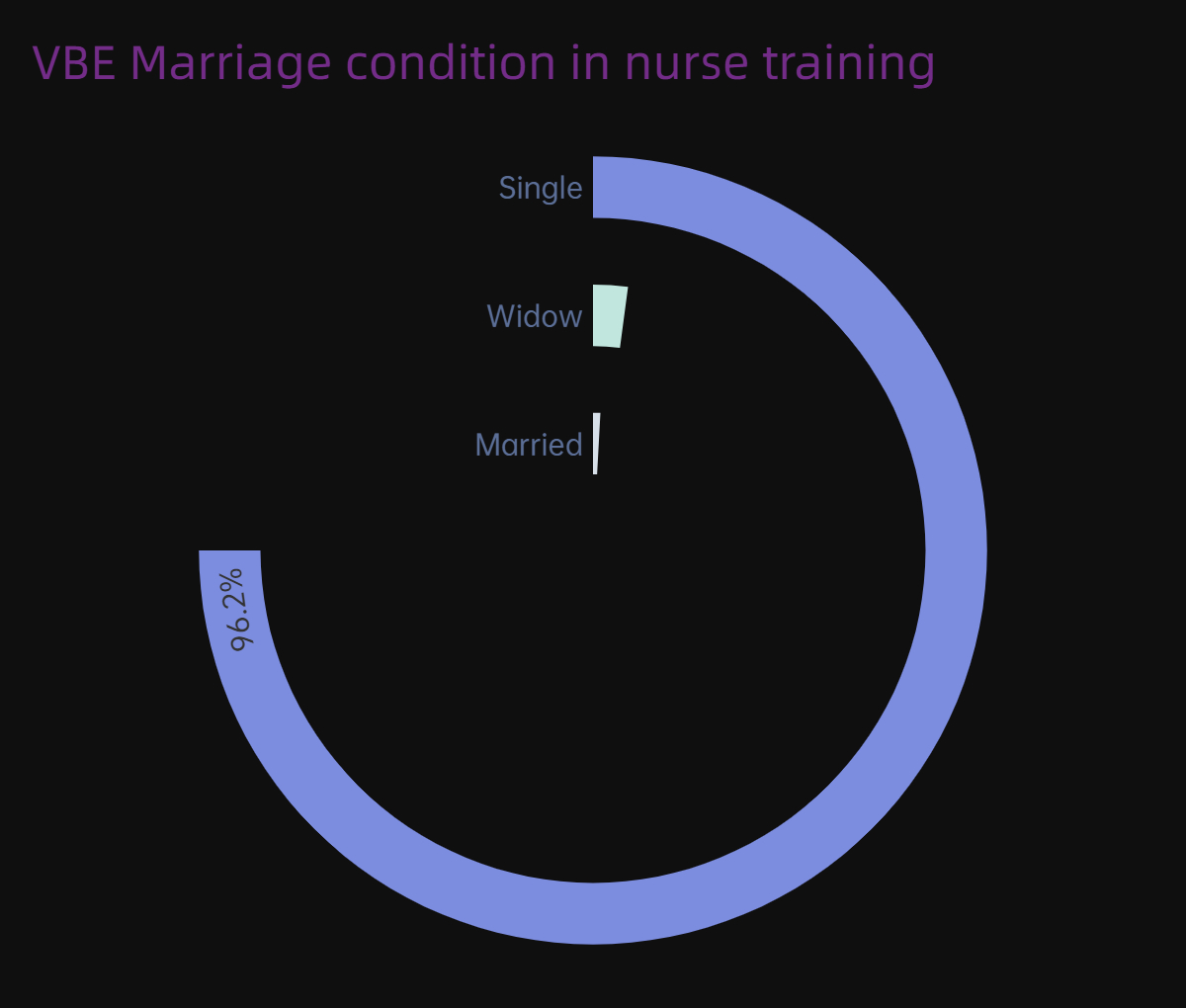

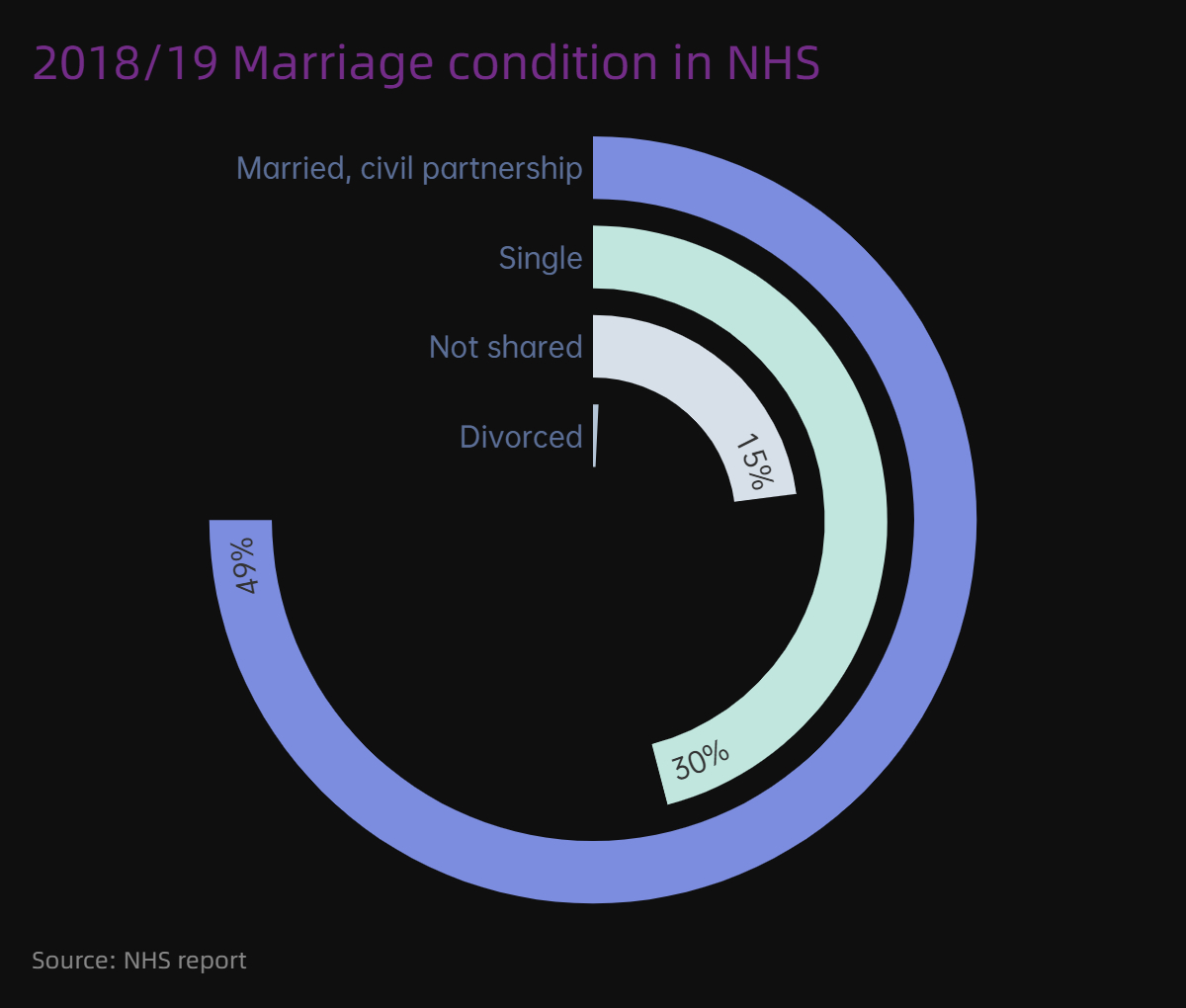

1. Marriage Condition: Past vs. Present

From the data we collected, 96.2% of people are “single”, while the proportions of “widows” and “married” are extremely low. Even the samples taken after 1895 were all single.

Now, a new pattern has emerged in the marital status data. For marriage conditions now like in 2018/2019, nurses who were married or in a civil relationship accounted for the largest proportion, about 40% or more. Single nurses lag slightly behind, ranking second at about 30%. The correlation between marital status and the profession of nurse is somewhat weakened.

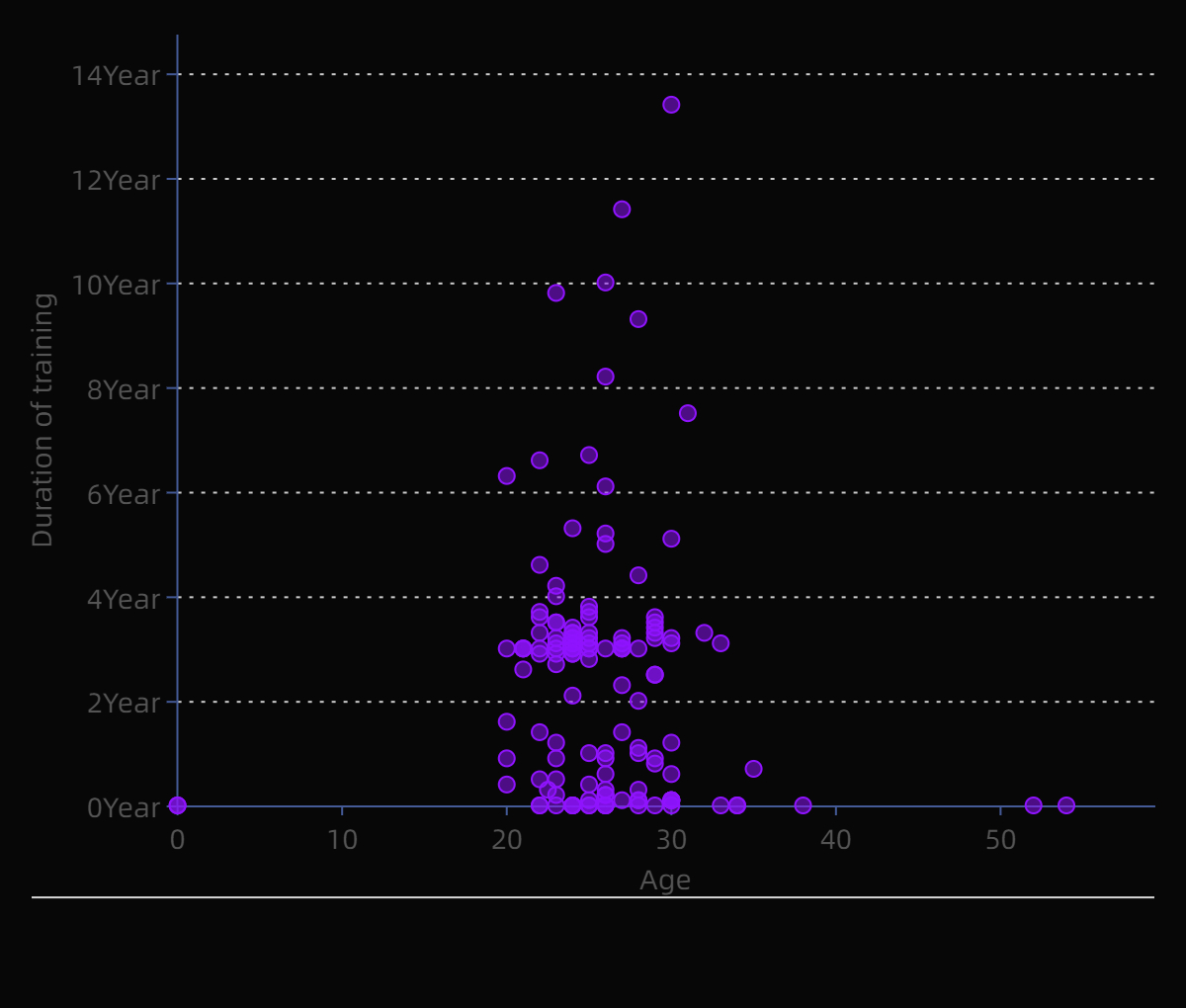

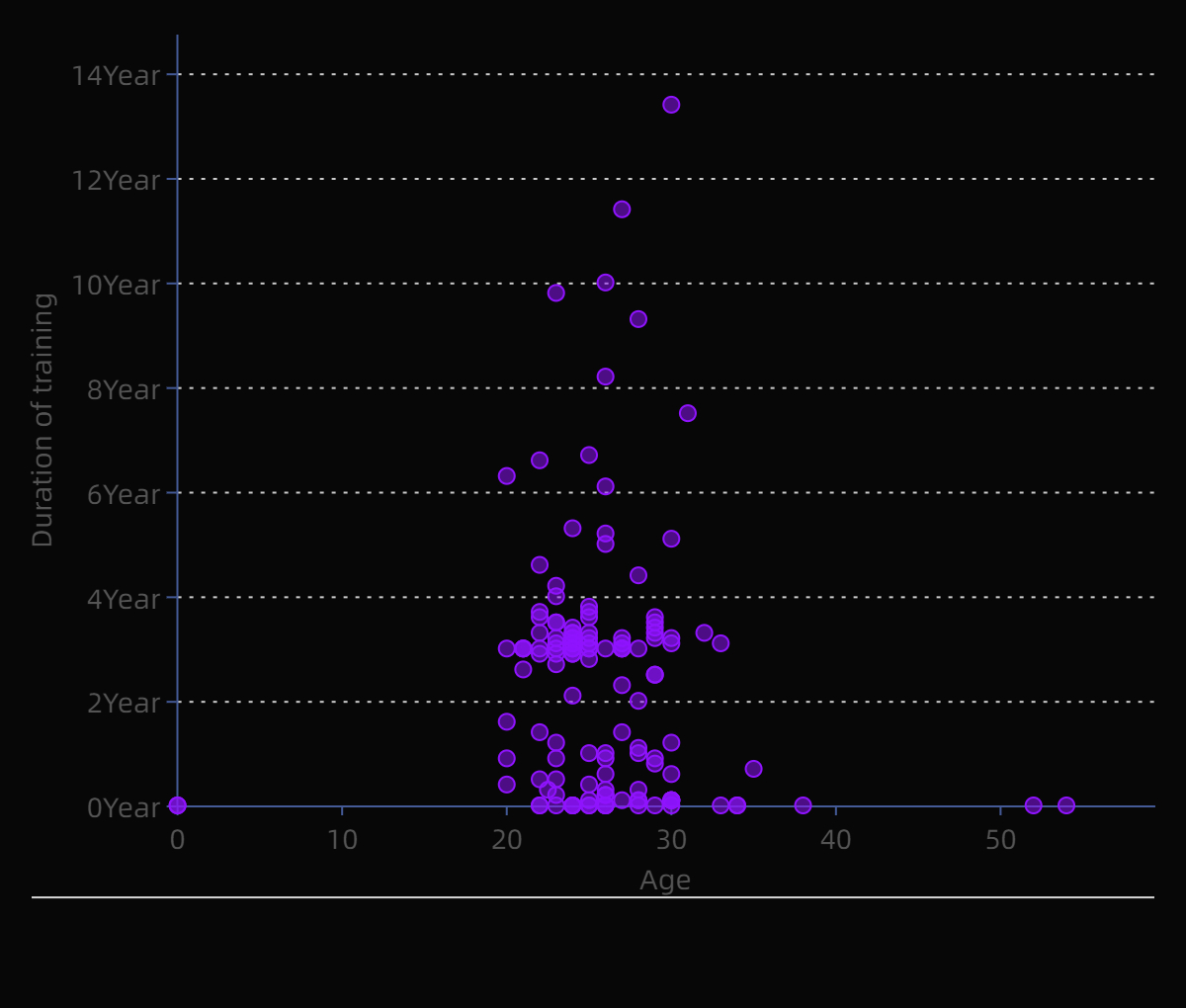

2. Training Age: Past vs. Present

Through data analysis, the largest proportion of nurses in the Victorian era were women between the ages of 20 and 30, accounting for 93.64%.

Today, according to the NMC register, the largest age group of registered nurses in the UK is the 21-40 age group, with 336,396 registered professionals, accounting for 42.66% of the statistical population. Registered nurses aged 41-55 account for 36.17%, which is very different from the past. Youth is no longer a characteristic of nurses.

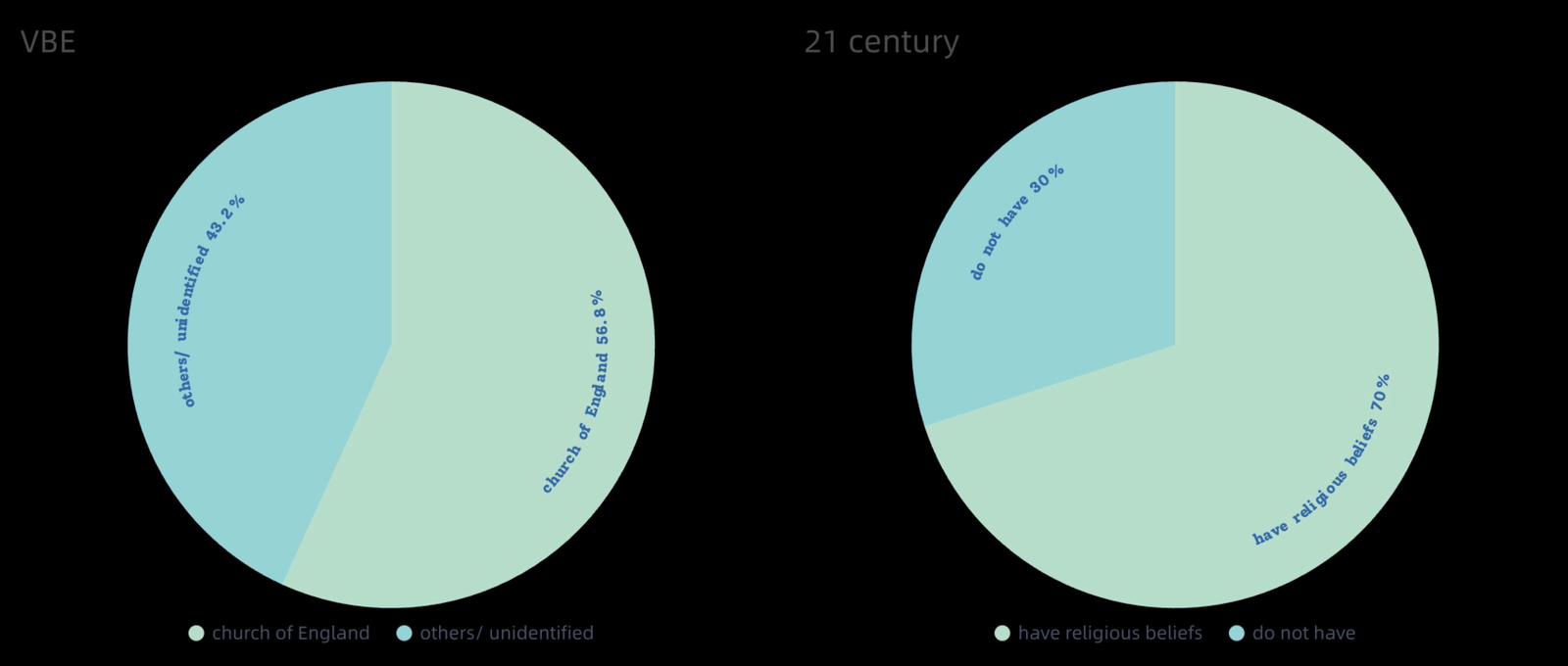

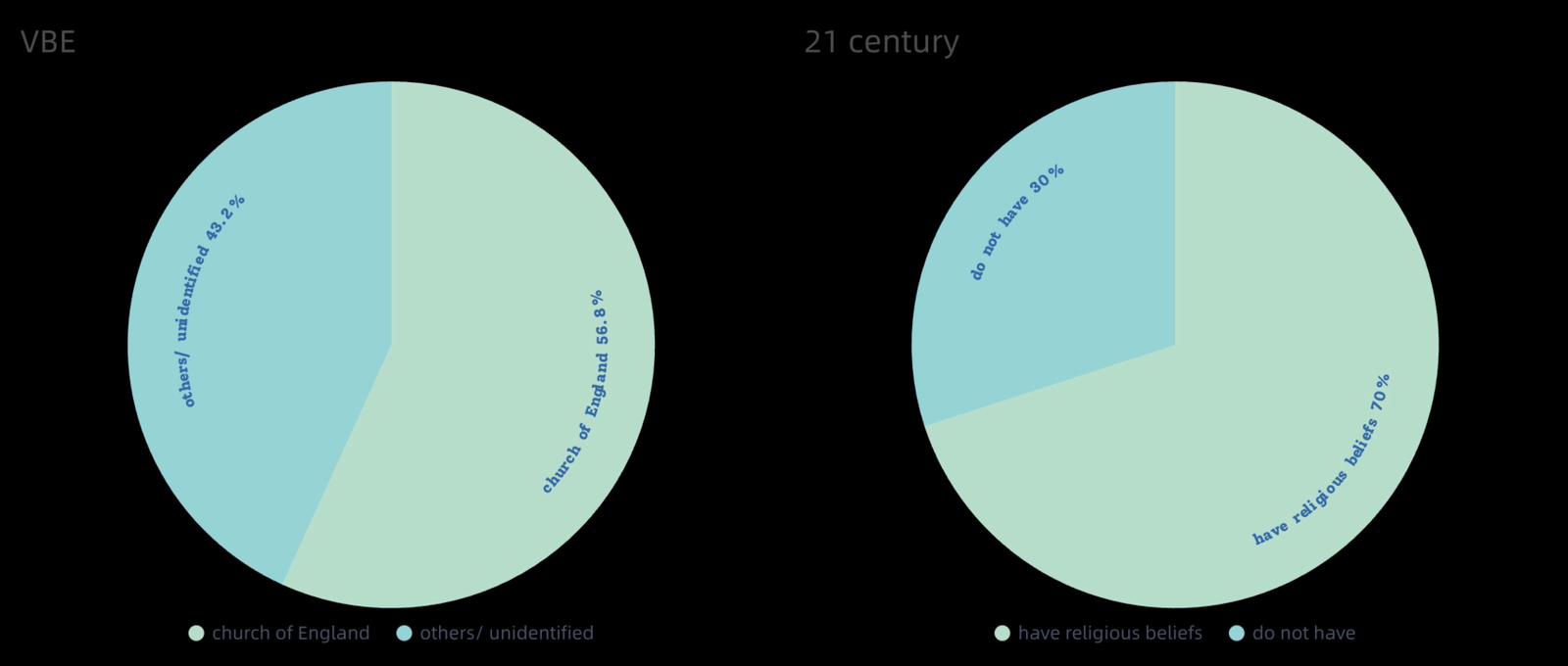

3. Religion Condition: Past vs. Present

It is estimated that around 1870, 57 per cent of nurses in the existing data were religious. It should be noted that this figure is only for those who volunteered their religious beliefs, and about two-thirds did not disclose their religion, so there is inevitably a degree of bias in the data.

However, in 2014 approximately 70 percent of NHS members had a religious affiliation. Multi-faith staff networks and chaplaincy departments continue to play a key role in providing care and support to staff, patients and their families, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

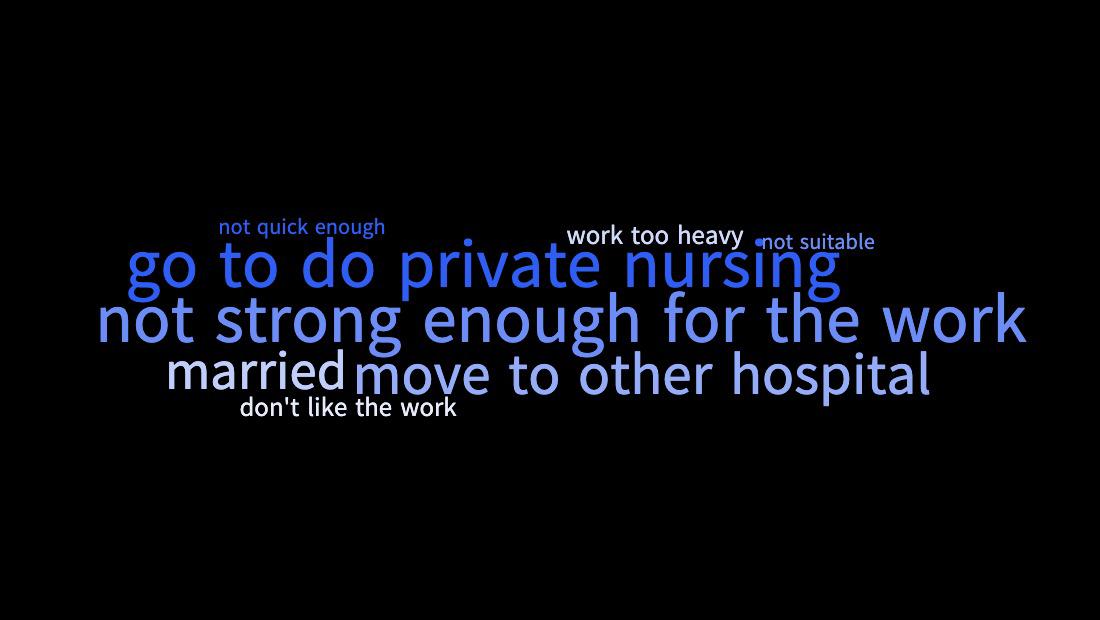

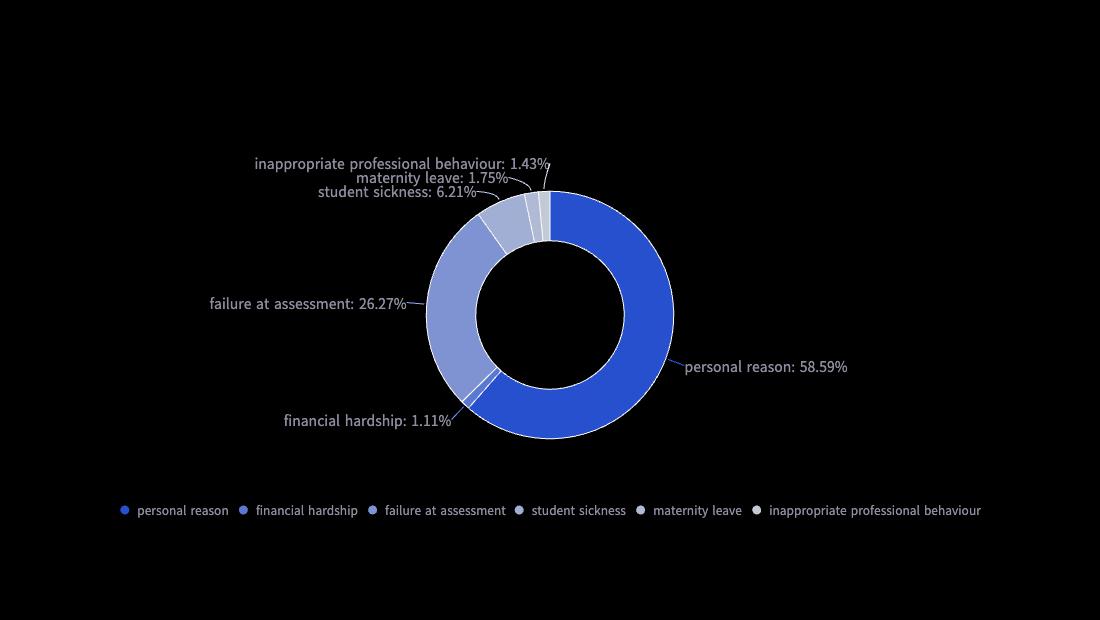

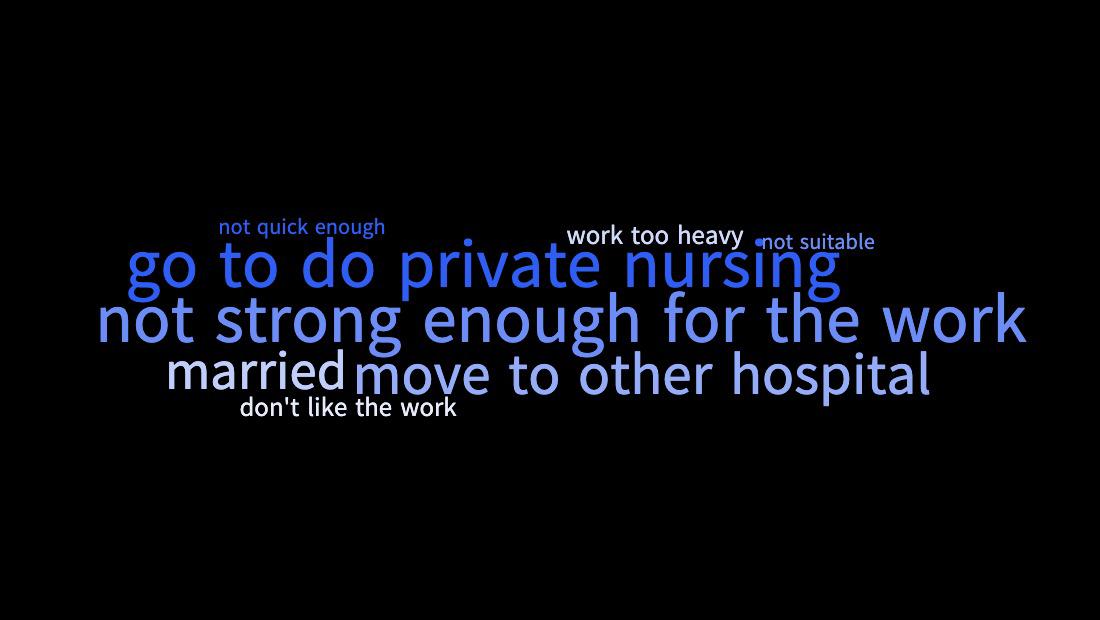

4. Reasons for Dropping Out from Training: Past vs. Present

In the past, the main reasons for nurses leaving their original positions were personal job transfers, marital status, and not having enough confidence to continue working. In addition, not being suitable for nursing work or personal career interests may also affect an individual’s resignation.

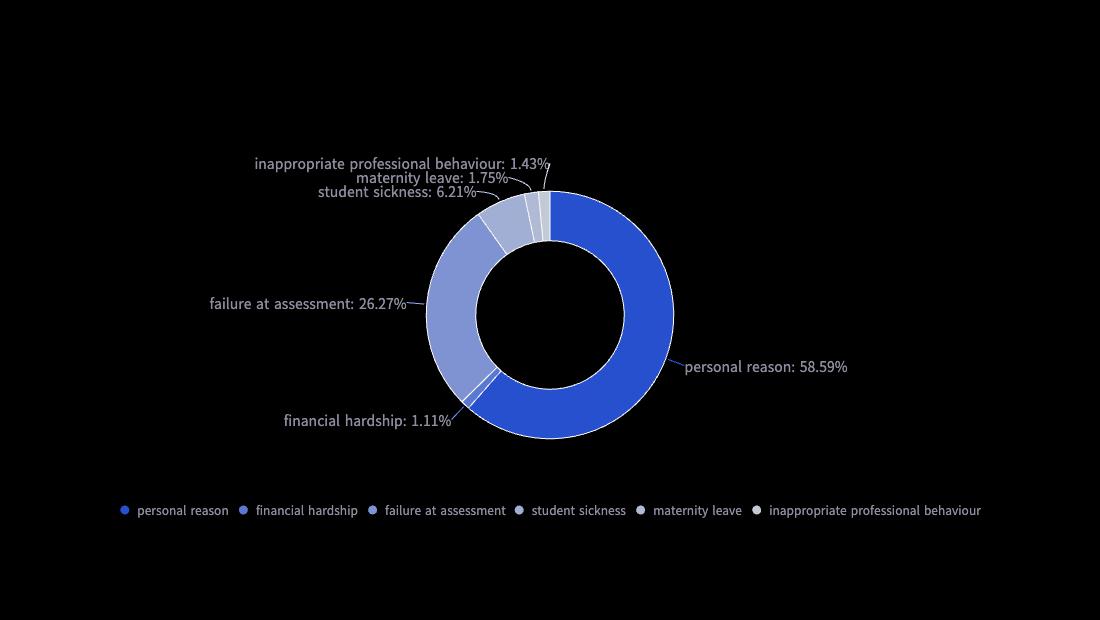

Let’s take a look at the data now. Figures obtained by the Care Standards and Health Foundation in 2019 show that the average attrition rate of nursing students in the UK is 24.0%. A similar analysis conducted last year showed the dropout rate for courses completed in 2017 was 24.8%.

As far as the factors that lead students to leave are concerned, personal reasons account for a large proportion, but more detailed information is not available. In addition, failure in course assessment is a very eye-catching factor. This shows that the nurse training and assessment system occupies a more important position than in the past, and is more rigorous and complete.

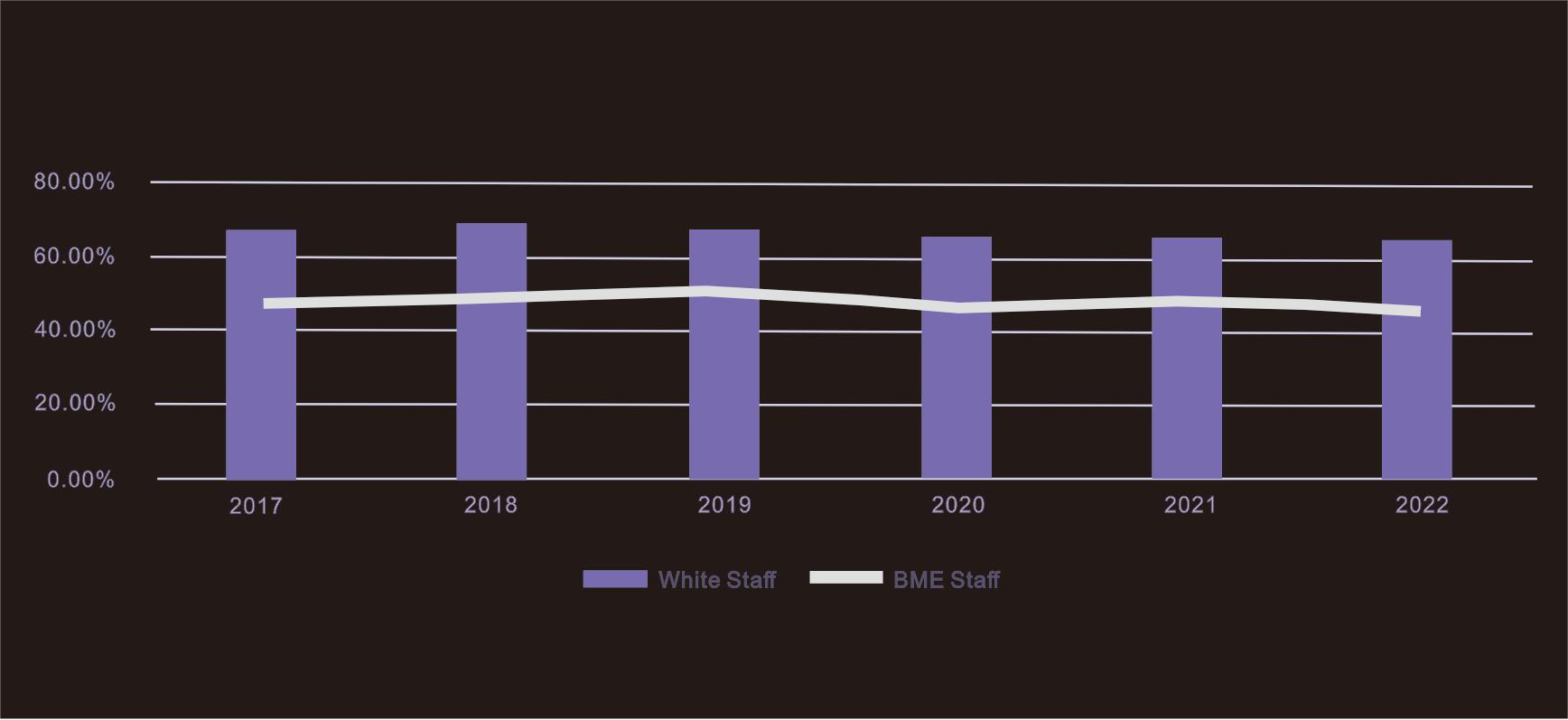

5. Perceptions of Career Progression Equality and

Promotion Opportunities by Ethnicity

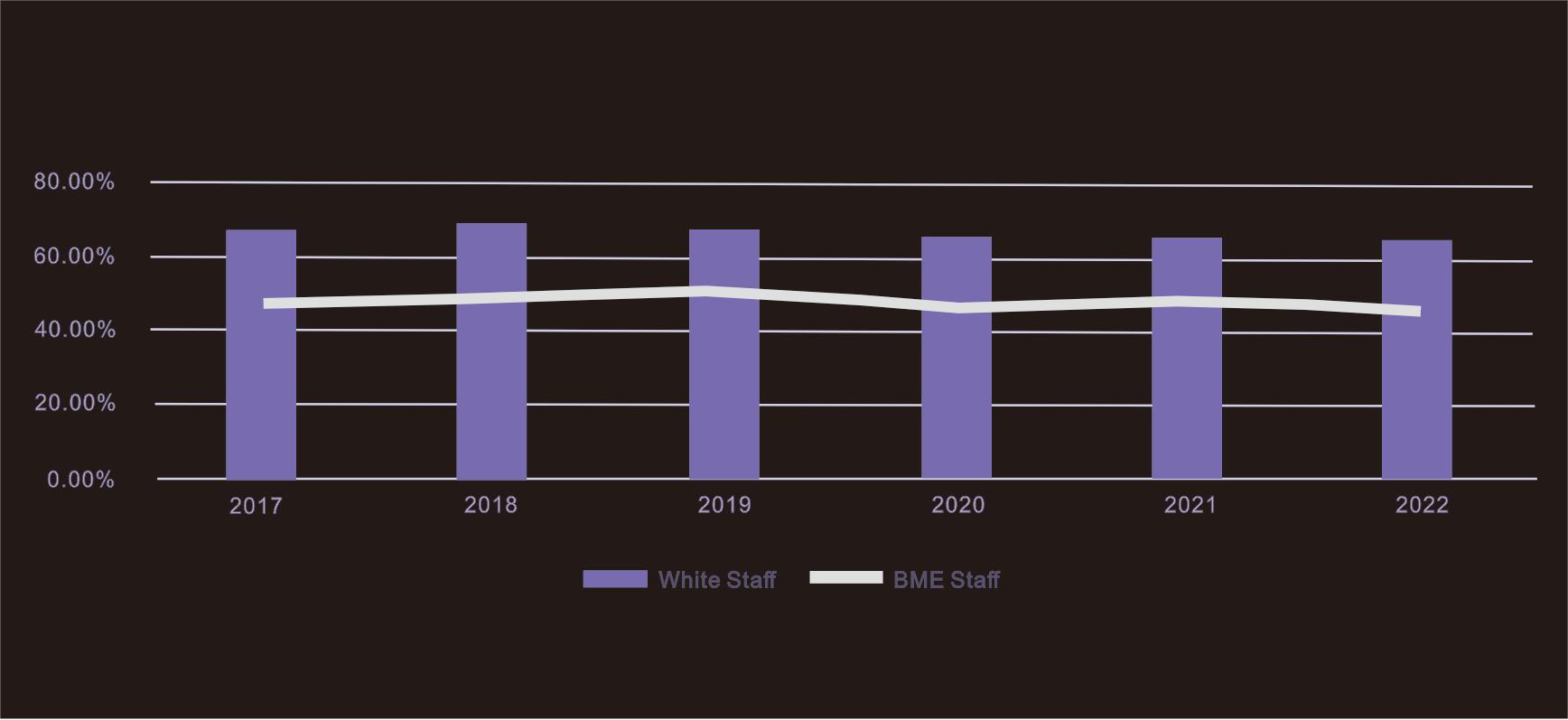

NHS Staff Survey 2022 - % of staff believing equal opportunity for career progression and promotion (NHS Foundation Trust)

The image displays a bar graph with line overlays, detailing the results of the NHS Staff Survey 2022 regarding staff beliefs in equal opportunities for career progression and promotion. The data covers a six-year span from 2017 to 2022, differentiating between White staff and BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) staff.

The percentage of White staff who believe in equal opportunities for career progression starts above 60% in 2017, slightly declines in 2018, but then shows relative stability around 70% in subsequent years. This suggests that the majority of White staff consistently perceive that there is equality in career advancement opportunities within the NHS.

The perception among BME staff starts at a lower point, around 40% in 2017, sees a significant increase in 2018 to nearly match that of White staff, and then stabilizes around 60% for the following years. However, it’s notable that this percentage remains consistently lower than that of White staff throughout the years, indicating a persistent disparity in the perception of equal opportunities for career progression.

6. Training Gender Distribution: Past vs. Present

According to our statistics, all nurses in the Victorian era were women. Figures released by the NHS on Women’s Day 2018 show that although nurses are still predominantly female, the gender gap is closing, with 89% of nurses and health visitors being female and 11% male.

Conclusion

Visualising data is a reiterative method of analysis and categorization, an essential tool in the digital era. Visual representations empower viewers to discern trends and insights swiftly, bypassing complex data manipulation. These graphical depictions transcend textual data in accessibility and engagement, resonating with the brain’s predilection for imagery and infusing data presentation with diversity and intrigue.

Our comparative analysis delves into historical and contemporary data, exploring marital status, age at entry into training, religious beliefs, reasons for leaving training, and gender distribution in training. Historically, the nursing sector favoured younger, unmarried women, echoing the societal expectations and norms of the era. Interestingly, religious adherence was lower than expected, a detail that might relate to our statistical methods; this will be further explained later. Personal competence was frequently cited as the reason for leaving training programs. Contrastingly, contemporary data heralds an era of heightened diversity in nursing. There is an increased male presence, a shift towards older age demographics, and a transition from predominantly single to married nurses.

Intriguingly, we’ve observed an internal NHS staff survey focused on the belief in equal career opportunities. The very existence of this survey underscores the NHS’s acknowledgement of the critical importance of diversity. It has given BME staff a stronger platform to voice their opinions on career advancement. The marked increase in BME staff believing in equal opportunities in 2018 is indicative of the NHS’s proactive approach to these viewpoints, highlighting its dedication to fostering a work environment where diversity is not merely recognized but actively supported and advocated for.

REFLECTION

Unfold the Story

The development of the nurse training record of Leeds General Infirmary in the 1800s, especially during the Victorian British Era, reflects not only the change in the number of nursing trainees but also the social norms at that time.

As mentioned in the former contexts, women in the Victorian British Era (VBE) chose to register the nursing training and start the job due to their living conditions and awareness. In recent years some scholars may have held the view that nursing is a female-dominated career which might affect the gender ratio in such workplaces, yet favouring males in the nursing area is inappropriate as this might become the barrier to eliminating gender stereotypes in nursing places (McLaughlin et al., 2010).

We acknowledge that the existing gender issue in the nursing workplace may potentially lead to discrimination and prejudice towards male workers as well, however, we should not forget the fact that females who lived in VBE were strictly constrained and considered nursing to be the only ideal occupation. This also contributes to the result that the nursing field is now dominated by females, to some extent. Other than nursing occupation, such circumstances appear to have an impact on employees working in other workplaces.

Gender inequality is never a simple problem that can be roughly discussed. Gender stereotypes and discrimination still tend to be barriers preventing women from getting what they can originally achieve, and some of them are even unequally considered to be unable to handle men’s jobs (Heilman, 2012).

“When they seek male gender-typed positions, they are prone to being seen as incompetent to handle them. When they choose to deviate from the set of behaviours deemed acceptable for women, behaviours that often are inadequate in the work context, they appear to pay dearly for their transgression.” (Hellman, 2012)

As for Western countries, racism and corresponding inequality tends to be the key issue in societies. In this research regarding the nursing field, while we were browsing the NHS record regarding inequality issues, the BME (Black and Minority Ethnic) table acts as an important part for us to analyse the inequality issue from another aspect. It is true that the percentage of staff who believe in equal opportunities and promotion provided in the NHS continues to be stable, the staff who are white have a higher trust than those who are BME.

We Experience It, We Feel It

We consider that:

“Inequality is a social issue and

public opinions sometimes overweigh the original data.”

As a group that consisted of Asian girls, compared to Western countries, we lack an understanding the racial inequality since Asian countries mostly have the same racial background. Even though we know the difficult surroundings they are in, we cannot go really deep to discuss other races since we are not experiencing their lives, thus the reflection may not be that comprehensive.

Nevertheless, we clearly understand what to mean by “gender inequality in workplaces”, and we even have a deeper empathy with this concept. Asian women face a harsher environment and competition even today. In China and Korea, women are resisting the unfair situation with their practical actions. Most typically, they choose not to give birth to a child to both keep their competence and ask for equal treatment. Moreover, Kim et al. (2022) researched female employees’ depressive symptoms regarding gender discrimination in workplaces, providing the conclusion that gender issues greatly affect female’s mental health in South Korea.

All team members expressed the same feeling that:

“Finding a job in our countries is surely difficult as women over 30 years old”

and “Males are owning their privilege in finding certain occupations.”

Therefore, eliminating gender inequality in the workplace will continue to be a critical issue in the future unless women feel they are getting what they should have obtained with their ability.

Exploring Data within the Context

Data has provided invaluable insights into uncovering the inequalities present in the nursing field both in the Victorian era and the present, shedding light on historical and contemporary events. However, the interpretation of data is heavily influenced by the social context in which it was collected.

For instance, a notable observation from examining the table of Leeds General Infirmary from the Victorian era reveals the exclusion of sex as a data point, while religion is included. This decision likely reflects the prevailing attitudes and priorities of the period. It’s crucial to delve into historical facts and contextual information to understand why such a decision was made.

Failure to consider the social context of the Victorian era would result in an incomplete understanding of the data, as it merely presents a partial snapshot of the past.

Moreover, it is essential to recognise that historical data cannot be directly applied to the present nursing field without considering the significant shifts in societal norms and values over time. In contemporary times, diversity has emerged as a crucial parameter for measuring equality in various fields, including nursing.

Unlike historical data, modern statistics often include demographic information such as ethnicity or nationality, reflecting the growing recognition of diversity’s importance in achieving equality. Neglecting to acknowledge this change could lead to erroneous conclusions, such as assuming that the nursing field has achieved equality simply by comparing present-day data with historical records.

“Data is not neutral and should not be viewed in isolation.”

As demonstrated by the examples above, the process of data collection is inherently influenced by the biases and assumptions of those involved (Crawford, 2013). These biases are not merely individual but are often rooted in prevailing stereotypes or dominant ideologies of the period (Devine, 1989). Consequently, the interpretation of data necessitates a critical and profound engagement with the social background from which it emerges.

Development of Media

Throughout the development of media, we’ve witnessed a profound transformation in how we collect, manage, analyse, and archive data (Neuman, 2010). These changes have left an indelible mark on our research methodologies, shaping the very essence of how we process information.

Our endeavour unfolded in three distinct phases as we embarked on processing historical data.

1: We ventured into the specialised archives of the University of Leeds, capturing images of the training books from Leeds General Infirmary. Faced with an overwhelming volume of information, we meticulously handpicked a selection of cases from each year.

2: The most arduous and time-intensive task awaited us in the subsequent stage: transcribing handwritten records into digital formats. Despite leveraging cutting-edge technologies, such as AI-based transcription programs, we encountered occasional inaccuracies stemming from inherent limitations. Nonetheless, we persisted, albeit with the necessity of discarding erroneous entries.

3: We embarked on visualising the compiled data, breathing life into the narratives concealed within the archives. In our quest to juxtapose past and present, we delved into contemporary databases, including the digital repository accessible through UCAS, housing comprehensive information on nursing school applicants. The ease with which we could navigate and extract insights from this digital repository underscored the transformative power of media technology.

In essence, the evolution of media technology has not only revolutionised the mechanics of data processing but has also endowed us with unparalleled efficiency and accessibility in our pursuit of knowledge.

References:

Crawford, K. 2013. The Hidden Biases in Big Data. Harvard Business Review. [Online]. 1 April. [Accessed 27 April 2024]. Available from: https://hbr.org/2013/04/the-hidden-biases-in-big-data

Devine, P. G. 1989. Stereotypes and prejudice: their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 56(1). pp.5-18.

Gebbels, M., Gao, X. and Cai, W. 2020. Let’s not just “talk” about it: reflections on women’s career development in hospitality. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management. 32(11). pp.3623-3643.

Gill, J. and Baker, C. 2021. The power of mass media and feminism in the evolution of nursing’s image: a critical review of the literature and implications for nursing practice. Journal of Medical Humanities. 42(3). pp.371-386.

Heilman, M.E. 2012. Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior. 32. pp.113-135.

Hu, Y., Shan, Y., Du, Q., Ding, Y., Shen, C., Wang, S., Ding, M. and Xu, Y. 2021. Gender and socioeconomic disparities in global burden of epilepsy: an analysis of time trends from 1990 to 2017. Frontiers in Neurology. 12. pp.643450–643450.

Kim, S., Won, E., Jeong, H.-G., Lee, M.-S., Ko, Y.-H., Paik, J.-W., Han, C., Ham, B.-J., Choi, E. and Han, K.-M. 2022. Gender discrimination in workplace and depressive symptoms in female employees in South Korea. Journal of Affective Disorders. 306. pp.269-275.

Lim, W.H., Wong, C., Jain, S.R., Ng, C.H., Tai, C.H., Devi, M.K., Samarasekera, D.D., Iyer, S.G. and Chong, C.S. 2021. The unspoken reality of gender bias in surgery: a qualitative systematic review. PLoS One. 16(2), p.e0246420.

McEnroe, N. 2020. Celebrating Florence Nightingale’s bicentenary. The Lancet. 395(10235), pp.1475-1478.

McLaughlin, K., Muldoon, O.T. and Moutray, M. 2010. Gender, gender roles and completion of nursing education: A longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today. 30(4). pp.303-307.

Neuman, W. R. 2010. Media, technology, and society: theories of media evolution. Michigan: University of Michigan Press.

NHS Digital. 2019. Marriage and civil partnership. [Online]. [Accessed 29 April 2024].Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/about-nhs-digital/corporate-information-and-documents/annual-inclusion-reports/our-workforce-demographics-2019/marriage-and-civil-partnership

Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust. No date. Our best staff survey results since 2018. [Online]. [Accessed 29 April 2024]. Available from: https://www.leedsandyorkpft.nhs.uk/news/articles/our-best-staff-survey-results-since-2018/#:~:text=If%20we%20 compare%20this%20 years,provides%20equal%20opportunities%20 for%20 career

Nurses.co.uk. No date. Stats and facts: UK nursing, social care and healthcare. [Online]. [Accessed 29 April 2024].Available from: https://www.nurses.co.uk/blog/stats-and-facts-uk-nursing-social-care-and-healthcare/

Paton, A., Fooks, G., Maestri, G. and Lowe, P. 2020. Submission of evidence on the disproportionate impact of COVID-19, and the UK government response, on ethnic minorities and women in the UK.

Peličić, D., 2020. Foundations of the aspect of health care and two hundred years since the birth of Florence Nightingale 1820-1910. Zdravstvena Zaštita. 49(4). pp.83-90.

Elements

Text

This is bold and this is strong. This is italic and this is emphasized.

This is superscript text and this is subscript text.

This is underlined and this is code: for (;;) { ... }. Finally, this is a link.

Heading Level 2

Heading Level 3

Heading Level 4

Heading Level 5

Heading Level 6

Blockquote

Fringilla nisl. Donec accumsan interdum nisi, quis tincidunt felis sagittis eget tempus euismod. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus vestibulum. Blandit adipiscing eu felis iaculis volutpat ac adipiscing accumsan faucibus. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus lorem ipsum dolor sit amet nullam adipiscing eu felis.

Preformatted

i = 0;

while (!deck.isInOrder()) {

print 'Iteration ' + i;

deck.shuffle();

i++;

}

print 'It took ' + i + ' iterations to sort the deck.';

Lists

Unordered

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Sagittis adipiscing.

- Felis enim feugiat.

Alternate

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Sagittis adipiscing.

- Felis enim feugiat.

Ordered

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Etiam vel felis viverra.

- Felis enim feugiat.

- Dolor pulvinar etiam.

- Etiam vel felis lorem.

- Felis enim et feugiat.

Icons

Actions

Table

Default

| Name |

Description |

Price |

| Item One |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

| Item Two |

Vis ac commodo adipiscing arcu aliquet. |

19.99 |

| Item Three |

Morbi faucibus arcu accumsan lorem. |

29.99 |

| Item Four |

Vitae integer tempus condimentum. |

19.99 |

| Item Five |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

|

100.00 |

Alternate

| Name |

Description |

Price |

| Item One |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

| Item Two |

Vis ac commodo adipiscing arcu aliquet. |

19.99 |

| Item Three |

Morbi faucibus arcu accumsan lorem. |

29.99 |

| Item Four |

Vitae integer tempus condimentum. |

19.99 |

| Item Five |

Ante turpis integer aliquet porttitor. |

29.99 |

|

100.00 |